LSST Camera arrives at Rubin Observatory in Chile, paving the way for cosmic exploration

The largest camera ever built for astrophysics has completed the journey to Cerro Pachón in Chile, where it will soon help unlock the universe’s mysteries.

The 3200-megapixel LSST Camera, the groundbreaking instrument at the core of the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, has arrived at the observatory site on Cerro Pachón in Chile.

The LSST Camera is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science (DOE/SC), and the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the DOE/SC. When Rubin begins the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) in late 2025, the LSST Camera will take detailed images of the southern hemisphere sky for 10 years, building the most comprehensive timelapse view of our universe we’ve ever seen.

“The arrival of the cutting-edge LSST Camera in Chile brings us a huge step closer to science that will address today’s most pivotal questions in astrophysics,” said Kathy Turner, DOE’s program manager for Rubin Observatory.

LSST Camera Arrives at Rubin Observatory

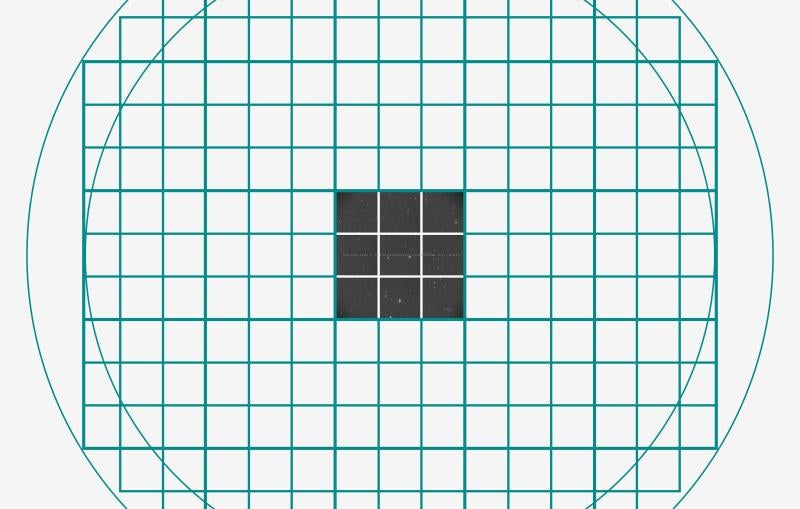

The LSST Camera – the largest digital camera in the world – was built at DOE's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California, and its completion after two decades of work was announced by SLAC early in April. This incredibly sensitive camera will soon be installed on the Simonyi Survey Telescope at Rubin Observatory, where it will produce detailed images with a field of view seven times wider than the full moon. Using the LSST Camera, Rubin Observatory will fuel advances – and brand new discoveries – in many science areas, including exploring the nature of dark matter and dark energy, mapping the Milky Way, surveying our solar system, and studying celestial objects that change in brightness or position. “Getting the camera to the summit was the last major piece in the puzzle,” said Victor Krabbendam, project manager for Rubin Observatory. “With all Rubin’s components physically on site, we’re on the home stretch towards transformative science with the LSST.”

The LSST Camera team at SLAC led the process of shipping the car-sized camera from California to Chile. This began by mounting it to a custom shipping frame and wrapping it in plastic electrostatic discharge material to protect it from moisture. Using an overhead crane, the team installed the frame that holds the camera into a 20-foot (about 6-meter) shipping container, modified with insulation on the walls and ceiling to ensure that the camera wouldn’t overheat, and with hardware to securely clamp the shipping frame directly to the container’s metal floor struts. The shipping container was also outfitted with data loggers, both on the camera frame and on the container itself, to monitor temperature, humidity, vibration and accelerations throughout the trip. A GPS tracking system was installed on the container so the team could pinpoint the camera’s location at any point on the journey.

Throughout the shipping process, the LSST Camera team adhered to a meticulously-prepared shipping plan – each decision outlined in the plan was intended to reduce potential risk to the $168 million camera. The team also had the benefit of a full dress rehearsal in 2021 when the camera mass simulator, a steel structure used for testing and balancing the telescope mount, was shipped to Chile. The mass simulator was also equipped with data loggers so the team would know exactly what conditions it encountered on its journey and could apply this knowledge when planning for the real camera. “Transporting such a delicate piece of equipment across the world involves a lot of risk. With ten long years of assembly work on the camera, culminating in a ten-hour flight and a winding dirt road up a mountain, it was important to get it right,” said Margaux Lopez, mechanical engineer at SLAC, who led the planning for the camera shipment. “But because we had the experience and the data from the test shipment, we were extremely confident that we could keep the camera safe.”

The LSST Camera, secure in its container, traveled on an air-ride-equipped transport vehicle to the San Francisco airport on the morning of May 14 for a chartered flight to Chile. There, it joined six other trucks worth of containers holding the camera’s filter exchange system and other ancillary equipment which had traveled the day before. After the camera was carefully loaded on the 747 cargo plane, two LSST Camera team members boarded the plane and settled into their seats for the 10-hour flight to Chile. “We were uncertain about the ‘jump seats’ we were promised on board, but they turned out to be plenty comfortable, and having two engineers on the plane was critical for loading and unloading,” said LSST Camera Project Manager Travis Lange. “The entire process was also incredibly exciting.”

The plane landed at Arturo Merino Benítez Airport in Santiago, the closest airport to the observatory that could accommodate a cargo plane of this size, at 4:10 a.m. on May 15. The camera container was loaded onto its own transport vehicle, one of nine trucks that drove in a slow convoy to the guarded gate at the base of Cerro Pachón, arriving in the early evening. Once the trucks were secured inside the gate, staff members retired to the nearby town of Vicuña for the night. In the morning, the vehicle carrying the camera began the 35-kilometer (21.7-mile) drive up to the summit, accompanied by pilot and tail cars. Driving slowly and carefully on the winding dirt road, the camera truck reached the summit in about five hours. The remaining trucks drove to the summit over the next two days on a schedule intended to minimize the disruption to other traffic on the mountain.

Upon its arrival at the observatory building, the camera was unloaded immediately into the receiving area on the third level and moved into the observatory’s white room, which offers a controlled environment with no airborne contaminants. There, it was inspected by the Rubin Observatory Commissioning Team and pronounced visibly intact. The team also downloaded the data from the data loggers and verified that the camera hadn’t encountered any unexpected stresses. “Our goal was to make sure the camera not only survived, but arrived in perfect condition,” said Kevin Reil, observatory scientist at Rubin. “Initial indications – including the data collected by the data loggers, accelerometers, and shock sensors – suggest we were successful.”

The LSST Camera is the final major component of Rubin Observatory’s Simonyi Survey Telescope to arrive at the summit, and after several months of testing in the observatory’s white room, the camera will be installed on the telescope along with Rubin’s newly-coated 8.4-meter primary mirror and 3.4-meter secondary mirror. Stay tuned for updates in the coming months as the LSST Camera – and Rubin Observatory – get closer to carrying out their transformative mission.

This article is based on a release from Rubin Observatory.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

Vera C. Rubin Observatory is a federal project jointly funded by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy Office of Science, with early construction funding received from private donations through the LSST Discovery Alliance. The NSF-funded LSST (now Rubin Observatory) Project Office for construction was established as an operating center under the management of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA). The DOE-funded effort to build the Rubin Observatory LSST Camera (LSSTCam) is managed by SLAC.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.